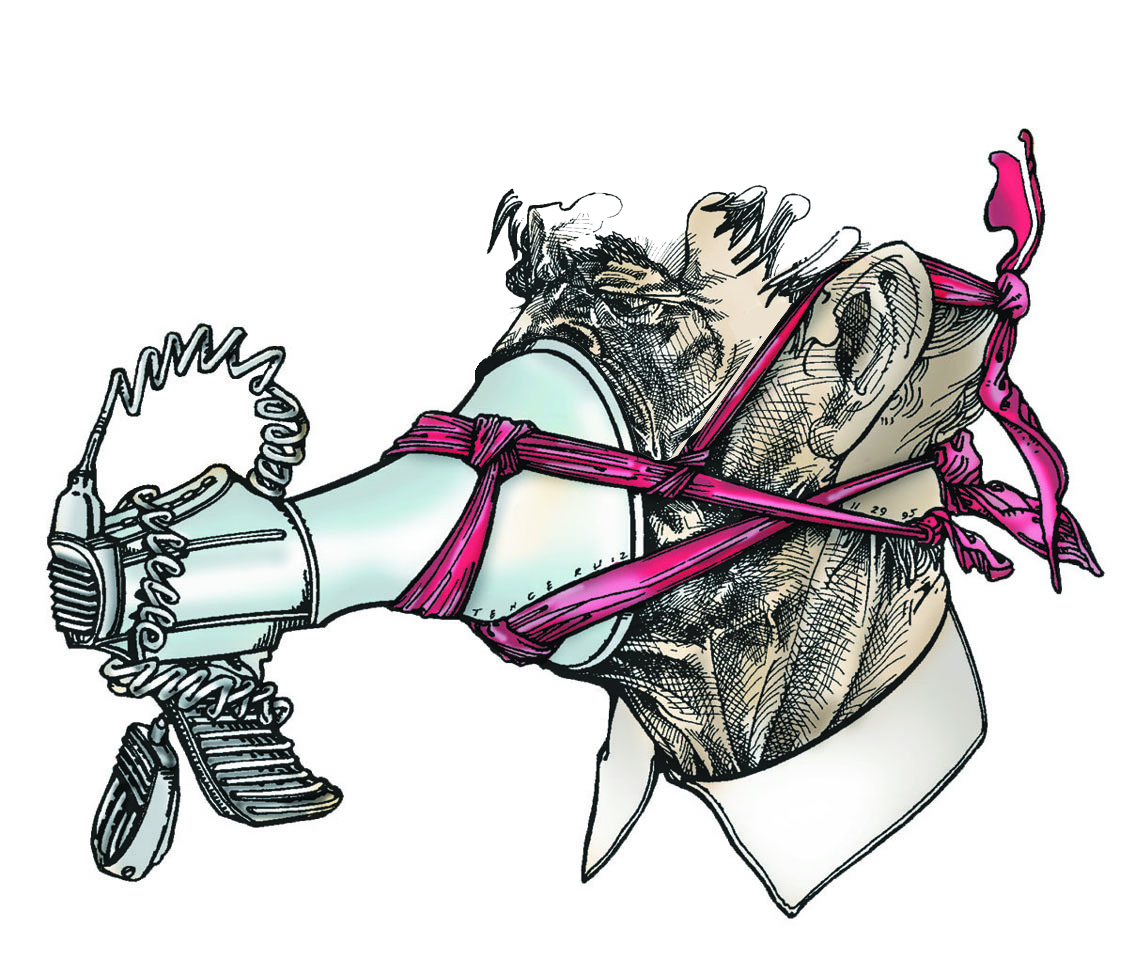

Don't act on the Act

Nepal’s governments have been biologically incapable of going to the root of any issue to find solutions. Instead, they introduce knee-jerk rules and banket bans that impinge on citizens’ rights.

The latest is the 11th amendment to the National Broadcasting Regulation in the Nepal Gazette. Like all previous ill thought out rules, this one is vague, contradictory, and unconstitutional.

The new amendment seeks to regulate Over the Top (OTT), Video on Demand (VOD) and internet television in Nepal. OTT is the service of displaying tv programs through the internet without using direct-to-home cable or satellite. It also includes media streaming services through other online platforms.

Now, any individual or organisation uploading a video via internet tv ‘on a regular basis’ needs to register. The licensing fee is Rs500,000.

The National Broadcasting Regulation is concerned with frequency allocation, not the internet. Regulating net content is not the purview of broadcast rules.

Advocate Prabin Subedi explains that the National Broadcasting Act does not regulate the internet. The government is trying to restrict the freedom of choice of citizens.

Any new law should either try to solve a problem or to facilitate a solution. But this is not just a clumsy attempt to restrict freedom of expression, but a blunt sword that can be used to go after anyone the government does not like. For example, what is a ‘regular broadcast’? Once a month? Once a week? When is an occasional post ‘regular’?

Even if it is to regulate ‘regular’ social media content, it should go through an internet specific law like the proposed Information Technology Bill. If it is about a tax on the earnings of online/social media it should be governed by corporate or taxation laws, explains Santosh Sigdel of Digital Rights Nepal.

Read Also: Gagging the press in installments, Sewa Bhattarai

By its very nature, the internet is an open ecosystem where people can communicate openly. Nepal's Constitution guarantees freedom of expression, and the country is also party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Article 19.

The amendment is against the Constitution because it limits freedom of expression. This is like needing a license to speak up.

After a public outcry, officials have tried to justify the amendment. But even if this is an attempt to curb fake news, open defamation and mala fide YouTube videos, it is crude and ham-handed. Instead of introducing draconian regulations, the emphasis should have been on spreading media literacy among citizens.

Sigdel told us the problem is that the government just does not understand the Internet’s convergence of text, video, audio and graphics. It is still trying to regulate them individually. It is clear that in this year of elections, politicians are concerned about the influence of social media content.

“Content cannot be regulated by state’s intervention. Most people can distinguish between genuine and fake news on YouTube, and we can create awareness through media literacy,” says Subedi.

Nepal appears to be following the example of its neighbours in subduing internet content. China has its Great Firewall, and last year India introduced controversial rules that have been used selectively to target opponents while allowing hate speech on other platforms. In February, Bangladesh came up with a draft regulation similar to India’s IT rules to curb social and digital media including OTT platforms. It is as if countries are exchanging notes on the most effective way to muzzle the media.

Successive governments in Nepal have tried to constrict the public sphere, the right to privacy and media freedom through various bills and regulations. Their vagueness is deliberately designed for arbitrary application against people the government does not like.

Nepal today stands as a beacon of press freedom in a region where the mediascape is increasingly constricted. Our lawmakers and bureaucrats should abandon the notion that they can suppress free expression just because other countries have.

Read also: Protecting free speech on Nepal’s cybersphere, Sabina Devkota

writer

Sahina Shrestha is a journalist interested in digital storytelling, product management, and audience development and engagement. She covers culture, heritage, and social justice. She has a Masters in Journalism from New York University.