The vagaries of fate

In her last column, Lisa Choegyal takes us on the Trans-Siberian Railway during the Soviet days

It was my Dr Zhivago fantasy period, and I had this wild idea that it would be compelling to travel solitary by surface all the way from Japan home to Britain – in winter.

‘How I envy you that railway journey,’ wrote Jan Morris, who fully appreciated the ‘special grace’ of travelling alone. Several days were spent transiting by train the massive expanse of the Soviet Union, and an uncertain seasonal ferry across the Sea of Japan to the east Siberian port of Nakhodka.

We disembarked at Omsk, or was it Tomsk, and the teeth-aching cold was such that breath crystalised and tongues froze if anyone was unwise enough to open their mouth. The grey platforms, steaming wheels and stolid Soviet silhouettes were discouraging, and I quickly climbed back into the carriage.

I remembered that time on the Orient Express when helplessly I watched the train with all my worldly belongings aboard chug out of the station – the stuff of nightmares – only to miraculously reappear after a few panicked devastating minutes. Character building stuff.

I had no such alarms on the Trans-Siberian, just surviving the bitter sub-zero temperatures every time I ill-advisedly alighted at a halt, and navigating the food where an expansive menu always seemed to have everything ‘off’ and only thick soup ‘on’. This became routine in the prescribed Intourist world of Soviet tourism, and was rather alarming at first. I adapted fast.

Frozen rivers became smooth wayfares for the winter trucks, and across a pristine snowfield from the relative comfort of my second class sleeper I witnessed a pack of wolves fleeing at the sound of our monstrous approach. The rich biodiversity of Lake Baikal was a disappointing expanse of frozen ice, fringed in skeletons of willow trees under a threatening sky. ‘The earth … spell-bound in a death-like winter trance,’ in the lone walker words of Kenneth Grahame.

The train windows were permanently edged with ice and outside the monochromatic views were truly bleak, but inside the atmosphere was cosy and encompassing. Large Russian ladies carried covered baskets of black bread and strong sausage with which I was plied.

Without any common language it did not take long to realise that these robust figures were worried about my slender frame – at nearly six feet tall and nicknamed 'hatini' back at Tiger Tops in Nepal, I was unfamiliar with feeling dainty and delicate, never before nor since.

It was the winter of 1974 and I was returning from Nepal — the long way round. Following a solitary trek to Jomsom and an interlude in Kathmandu as an unsuccessful hippie, I had been working in Chitwan for a few marvellous months until the monsoon floods drove us out of the national park.

A series of adventures had landed me in Tokyo, including a spell selling diamonds with a couple of canny cockneys in Malaysia and Singapore, hanging out with bankers in Hong Kong, and devouring the sophisticated design and elegant intricacy of Japan’s ancient cities.

But my mind was occupied with schemes as to how to wangle my way back to Nepal and the conservation tourism work that had captivated me. It would take me less than a year. Looking back, we can see our lives hang by a thread on seemingly random decisions and the vagaries of fate that could not have been predicted.

That 1974 me, dreaming of the Himalaya in another railway carriage heading home from Moscow and Leningrad through Poland to another ferry across the choppy English Channel, would have been astonished at what lay ahead.

Fast forward to a couple of years ago, and the long afternoon shadows of the Indian Embassy Residence reached us across the gently sloping and perfectly mowed lawn — white stucco columns, spreading balconies and blatant colonial blustering of the two story house first constructed for the British and handed over shortly after Independence.

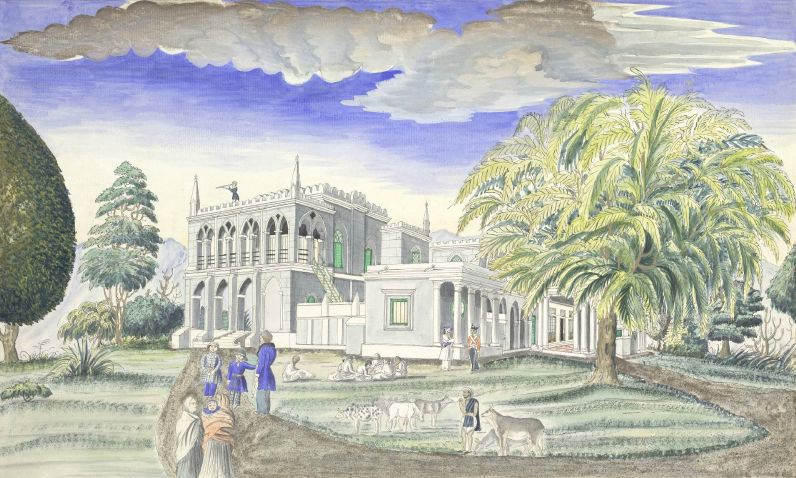

I felt the distant presence of Brian Hodgson, the first British resident to inhabit the bequeathed badlands of distant Lazimpat, depicted in this garden supposedly with his Moslem consort. The contemporary drawing has a picturesque primitive charm, that seemed strangely distant from the gathering of literary luminaries.

The scent of roses mingled with that of my be-saried neighbours as we settled into the lushly padded chairs to enjoy a discourse on a small stage in front of the begonias. The subject was a book on mid-twentieth century life in the Kumaon hills by an esteemed Indian author swathed in cashmere and silk.

‘I can’t cope with this nostalgia nonsense.’ The Indian ambassador’s face beneath his perfect turban was crumpled with nuance. ‘We have to move forward from the Raj, away from those battalions of white men, into the current reality. Romanticising the hill station life into a forgotten yesterday does none of us any favours.’ He fixes me with a steely glare. ‘Nor all that Raj rubbish about polo in the jungle.’ My most recent column in Nepali Times.

I have no trouble agreeing. Wrestling with nostalgia has been my fortnightly task in this space for the last three years. I prefer to think of my articles as recalling living history, as background context to today’s evolving environmental issues and tourism landscape.

Without even a nod to nostalgia, there are many hardnosed lessons to be learned from the impressive track record in tourism and conservation of which Nepal should be proud.

After 100 articles and three years, Lisa Choegyal is closing her So Far So Good fortnightly column. All her past pieces are available in the www.nepalitimes.com archives.

writer